Introduction: What Happened to Architectural Craft?

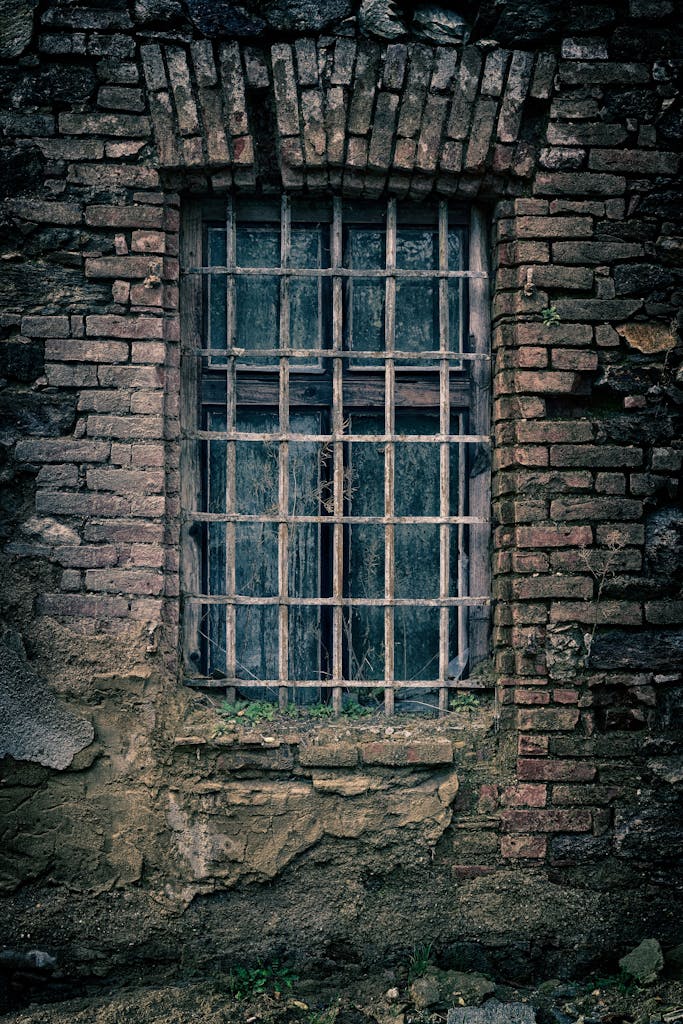

Architecture once celebrated intricacy — in carved woodwork, delicate ceiling medallions, and thoughtful spatial hierarchies like service stairs and transoms. These obsolete architectural details weren’t just aesthetic flourishes; they defined how people interacted with buildings, revealed social structures, and conveyed craftsmanship and permanence. Today, most of them are missing from new construction.

This article explores these vanishing elements: why they disappeared, what their loss reveals about contemporary design, and whether reintroducing them could restore a richer spatial language in today’s architecture.

Ceiling Medallions: Where Beauty Met Utility

Ceiling medallions — ornate rings of plaster or wood surrounding hanging lights — were once a staple of residential and civic architecture. They functioned as focal points and decorative centerpieces in rooms, often hand-molded with floral or geometric motifs.

Why they became obsolete:

- Recessed and ambient lighting removed the need for hanging fixtures.

- Minimalist trends dismissed ornament as unnecessary.

- Plasterwork craftsmanship declined with labor and time constraints.

Ironically, in luxury interiors and boutique hotels, ceiling medallions are returning — often as lightweight, prefab pieces that reference the past without its labor.

Service Stairs: The Architecture of Class Division

Once essential in homes with domestic staff, service stairs allowed movement behind the scenes — connecting kitchens to upper floors invisibly. They embodied a spatial logic rooted in privacy and hierarchy.

Why they’re now obsolete:

- Social structures shifted; live-in staff declined.

- Open-plan layouts prioritize shared space and transparency.

- Accessibility codes favor unified circulation systems.

Still, some large villas or embassies quietly retain separate service routes — now justified through logistics rather than status.

Hand-Cut Joinery: The Lost Art of Crafting Connection

Before industrial adhesives and mass-produced fasteners, joints were architecture. From dovetails to mortise-and-tenon, these connections showed how structure and craft were inseparable.

Why they vanished:

- Prefabricated construction replaced site-specific carpentry.

- Fewer craftsmen are trained in traditional joinery.

- Cost and time outcompete beauty and longevity.

In timber-focused architecture, some firms are reviving these methods through CNC machining — blending tradition with digital precision.

Transoms and Clerestories: Passive Comfort Forgotten

Obsolete architectural details also include strategies for comfort without machines. Transoms — small operable windows above doors — once allowed cross-ventilation and light. Clerestories brought daylight into deep plans.

Why they disappeared:

- Air conditioning and artificial light became the norm.

- Open-plan designs removed many internal doorways.

- Code and budget reduced emphasis on operability.

Today’s passive-house movement is reclaiming such elements — not for nostalgia, but for energy efficiency and occupant well-being.

Built-In Niches and Furniture: Space Designed for People

Older architecture often included wall niches, alcoves, and built-in cabinets tailored to occupants. These were not add-ons but integrated design gestures optimizing both space and aesthetics.

Why they faded:

- Mass-produced furniture became more flexible and affordable.

- Developers prefer neutral, open interiors for resale.

- Custom millwork is expensive and time-consuming.

Yet in high-end residential and hospitality projects, built-ins are being reimagined as luxury rather than necessity.

Decorative Cornices and Mouldings: Framing the Volume

Cornices and mouldings once served to transition between surfaces, visually completing rooms and guiding the eye across a space. Their absence today reflects a broader loss of spatial articulation.

Why they’re obsolete now:

- Modern design avoids visual complexity.

- Builders use drywall and flush edges to cut time and cost.

- Market expectations prioritize clean lines over character.

But in adaptive reuse and boutique interiors, these features return as historical texture and architectural rhythm.

Why Do Obsolete Architectural Details Vanish?

The reasons span economics, labor shifts, taste, and technology:

- Efficiency over expression: Fast-track construction discourages intricate work.

- Modernism’s legacy: 20th-century ideologies dismissed ornament as inauthentic.

- Labor scarcity: Skilled artisans are harder to find and afford.

- Standardization: Mass production favors uniformity.

What results is a streamlined, often generic architectural language — efficient but less emotive.

What We Lose When Details Disappear

Obsolete architectural details once told stories — about who we were, how we lived, and what we valued. Their absence may make construction cheaper, but it also erases layers of meaning, beauty, and identity.

These details engaged all senses, gave each room a unique mood, and often carried cultural specificity. Their removal has flattened spatial experience and replaced memory with neutrality.

Are We Seeing a Return?

Some designers are reintroducing obsolete architectural details — selectively, adaptively, and often with new technologies. CNC routers simulate classic carvings. 3D printers replicate ornamental plaster. What was once crafted over weeks can now be installed in days — without losing poetry.

Movements like New Traditionalism and digital craft architecture propose a future where detail matters again, where ornament isn’t superficial, and where history has a voice.

Conclusion: A New Respect for the Obsolete

“Obsolete” is a relative term. Many architectural details have not died — they’ve been waiting. As we move into an era that values narrative, sustainability, and beauty, these lost elements offer lessons. They remind us that buildings aren’t just made to function — they’re made to feel.

By revisiting and reimagining obsolete architectural details, we may rediscover a deeper, more human kind of design.