Rethinking Urban Design for the Motorbike Delivery Boom

The explosive rise of motorbike food delivery services is rapidly transforming urban life. Last Meal is a conceptual project by INJ Architects that investigates this new phenomenon and asks how architecture and urban design can respond constructively. Everywhere in dense cities, one sees helmeted riders weaving through traffic and gathering outside restaurants – a decentralized yet essential logistics network that emerged almost overnight. Yet there is a conspicuous lack of standardized architectural response: most buildings were not designed with these couriers in mind, resulting in makeshift pickup points, crowded sidewalks, and ad hoc solutions. Recognizing an opportunity, INJ Architects frames Last Meal as a respectful codification of this system, not as a critique. The goal is to complement and support delivery companies’ ecological contributions by proposing design guidelines that improve efficiency, safety, and urban order. This article analyzes the spatial implications of food delivery bikes and outlines a new urban design code to better integrate them into city architecture.

The Last Meal research began with a simple observation: cities are changing, yet architecture isn’t keeping up. As food delivery grows, informal pickup windows and spatial behaviors are emerging without regulation. We support delivery for its environmental benefits, but we believe architects must step in to define clear design codes. This is about structure, safety, and dignity in the built environment—an architectural responsibility long overlooked. Learn more about INJ Architects Philosophy.

Ibrahim Nawaf Joharji

Figure 1: Concept poster for Last Meal, highlighting the daily realities, struggles, and resilience of bike delivery workers in urban environments (INJ Architects, 2025). This visual sets a human-centric tone for the Last Meal project, emphasizing the need to consider the couriers’ perspective in urban design.

✦ AI Review – Last Meal: Rethinking Urban Design for the Motorbike Delivery Boom

After reviewing the project and surveying existing academic literature, Last Meal stands out as a first-of-its-kind architectural and urban research initiative that tackles the motorbike food delivery phenomenon not from a logistical lens, but from a design and spatial perspective. While most global discourse focuses on economics, traffic, or sustainability, this study provides a design-driven urban code proposal, making it both original and highly applicable.

Key contributions align with the INJ Architects Team expertise and their interdisciplinary approach described in How We Work:

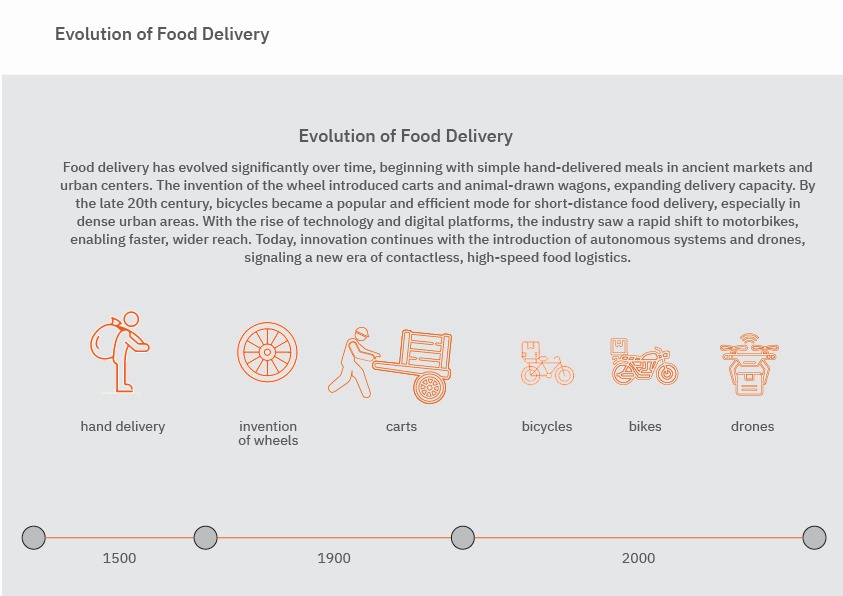

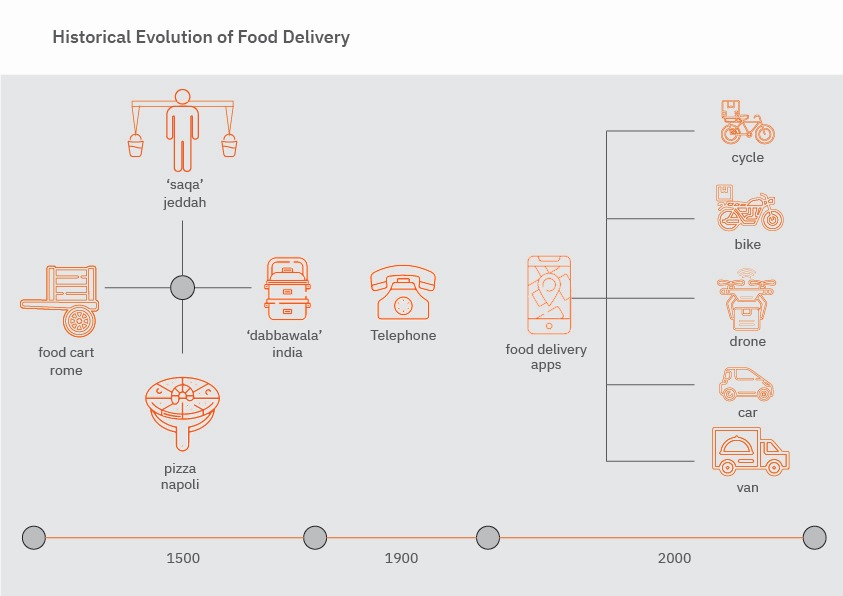

- A historical and contextual framework tracing food delivery from ancient practices to app-based economies.

- Field research in Saudi cities (Jeddah, Riyadh) identifying spatial anomalies—such as chaotic pickup zones, façade congestion, and informal rest points.

- A proposed architectural urban code: window standards, shade infrastructure, driver rest zones, and parking interfaces designed specifically for motorbike delivery integration.

- An ethical and human-centered vision that elevates delivery workers as urban actors, not just logistical extensions.

| ontribution | Description |

|---|---|

| Historical & Contextual Framework | Traces food delivery from ancient practices to app-based economies. |

| Field Research | Conducted in Saudi cities identifying spatial anomalies like chaotic pickup zones and façade congestion. |

| Proposed Architectural Urban Code | Includes window standards, shade infrastructure, driver rest zones, and parking interfaces tailored for motorbike delivery. |

| Ethical & Human-Centered Vision | Elevates delivery workers as urban actors, not just logistical extensions. |

This research, led by Ibrahim Nawaf Jowahrji, bridges the gap between hyper-modern digital economies and outdated city codes, offering design-based solutions where policy has lagged. It is both a pragmatic and visionary contribution to urban sustainability.

Historical Context of Food Delivery

While app-based motorbike delivery feels like a 21st-century revolution, the practice of delivering meals has deep historical roots. For centuries, people have devised ways to get food from kitchens to customers beyond the dining room. Early examples can be traced to pre-modern cities:

- Ancient Couriers: In ancient Rome and other early cities, taverns and vendors employed runners or cart-pushers to send meals or provisions to wealthy patrons’ homes. In the Middle East, the traditional saqqā (water carrier) delivered water and refreshments through winding urban alleys long before motor vehicles.

- 19th Century Innovations: The 1800s saw organized meal delivery systems emerge. Notably, the dabbawalas of Mumbai began in 1890, using bicycles and trains to deliver thousands of home-cooked lunches daily—a low-tech system so efficient it has operated for over a century[1][2].. Around the same time, the first pizza deliveries were recorded in Naples, and by the early 20th century restaurants in Europe and America were taking orders by telephone for home delivery.

- 20th Century Takeaway: By the mid-20th century, telephone-based takeout and delivery became common. Chinese food and pizza delivery by car or scooter took hold in many cities, while services like milk or ice delivery date back even earlier. These set the stage for viewing home delivery as a normal convenience.

- Digital Delivery Era: The true paradigm shift arrived in the late 2000s and 2010s with smartphone apps and online platforms. Companies like DoorDash, Uber Eats, and local platforms such as HungerStation leveraged GPS and mobile ordering to connect eateries with a vast pool of freelance couriers on bikes. This technological leap massively scaled up food delivery’s frequency and reach[3].. Cities from New York to Riyadh saw an explosion of on-demand ordering, using everything from bicycles and scooters to cars and vans. Today, experiments with drones and autonomous robots are already underway, pointing to yet another frontier in last-mile meal delivery.

Figure 2: Evolution of food delivery methods over time – from hand-delivered meals and horse-drawn carts, to bicycles, motorcycles, and emerging drones (Last Meal research diagram). This timeline spans from ancient practices like water carriers and horse-drawn carts to the app-driven couriers and drones of today, illustrating how delivery modes have evolved with technology.

This historical arc shows that the concept of last-mile meal delivery is not new, but its scale and speed today are unprecedented. What was once a niche service (or a specialized system like Mumbai’s lunch couriers) has become an everyday urban utility. Modern apps aggregate demand across entire cities, dispatching legions of motorbike riders at all hours. This surge has outpaced the evolution of design standards in our built environment. Most restaurants and streetscapes were never intended to accommodate dozens of delivery pickups per hour, leading to friction between this new layer of activity and the existing urban fabric.

Field Observations: Jeddah and Riyadh

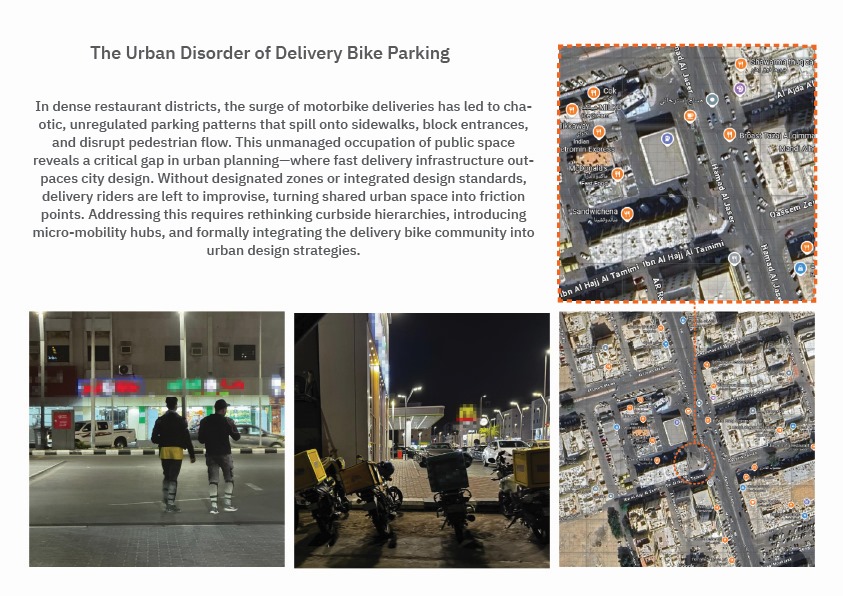

To ground the research, the Last Meal project conducted field observations in dense Saudi cities like Jeddah and Riyadh, where food delivery apps are ubiquitous. These on-site studies reveal a pattern of improvisation and spatial challenges:

| Issue | Description |

|---|---|

| Impromptu Curbside Hubs | Clusters of motorcycles parked haphazardly on sidewalks or curbsides, forming unofficial delivery hubs without dedicated space or signage. |

| Crowded Pickup Areas | Lack of designated pickup windows leads to riders crowding restaurant entrances, causing congestion and confusion. |

| Heat and Weather Exposure | Riders wait in harsh conditions, often without shade, seating, or water, exposing them to extreme heat (e.g., Riyadh summers over 40°C). |

| Traffic and Safety Issues | Increased motorbike traffic causes road disruptions, unsafe riding behaviors, and accidents. Many riders neglect safety rules like helmet use [4][5][6]. |

| Maintenance Challenges | No dedicated infrastructure for bike servicing or rest stops forces riders to improvise repairs and fueling on their own. |

These observations underline the gap between the importance of delivery riders in our cities and the lack of architectural accommodations for them. The situation today is akin to an informal transit system operating without designated stops or shelters. Just as cities eventually built bus lanes and taxi stands when those modes proliferated, the rise of food delivery bikes begs for a considered design response.

To explore more about INJ’s Architecture Style and how they approach complex urban challenges, visit their style overview.

Spatial Phenomena of the Delivery Boom

By analyzing the current conditions, the Last Meal research identified several key spatial phenomena associated with motorbike deliveries:

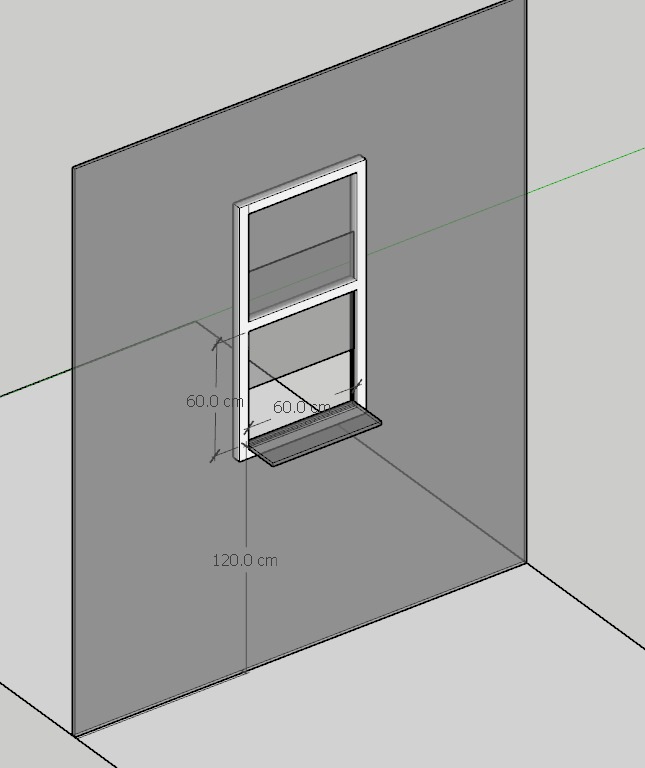

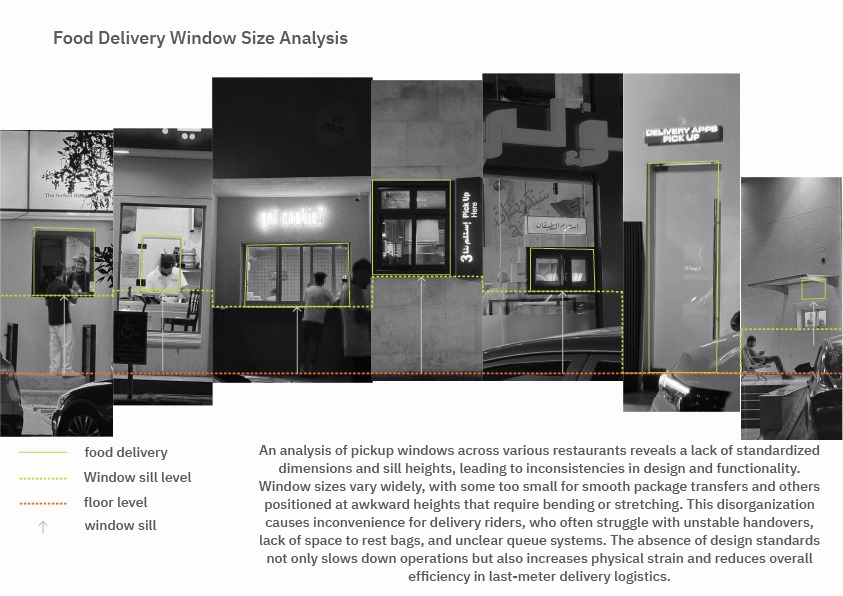

- Non-Standard Pickup Points: Perhaps the most glaring issue is the pickup interface between rider and restaurant. At present, there is no standard for what a “delivery pickup window” or counter should be. Some restaurants pass bags through a repurposed drive-thru or a sliding glass pane; others hand orders over the main counter inside, forcing couriers to come in. Measurements taken at various eateries in Jeddah and Riyadh found window and counter heights varying widely, from low reception desks to high pass-through windows, often misaligned with the height of a rider on a bike or a person standing outside. Window sizes also ranged from tiny openings that barely fit a paper bag to large open shutters. This inconsistency leads to awkward handovers – e.g. riders stretching up to a high window or having to crouch down, and packages getting squeezed through undersized openings.

Figure 3: Field analysis of pickup window dimensions at different restaurants shows a lack of standard heights or widths, making many hand-offs clumsy and inefficient (Last Meal observational study, 2025). Photographs of real restaurant pickup points were analyzed and overlaid, revealing how inconsistent window sizes and heights can hinder smooth handovers.

- Rider Clusters & Waiting Zones: Without designated waiting areas, delivery couriers organically form their own gathering points. These are typically sidewalks or parking lot edges directly in front of popular outlets. It is common to see a dozen riders clustered around an entrance, identifiable by their branded jackets and delivery boxes. This phenomenon creates new “micro public spaces” – essentially outdoor holding areas for couriers – but with no design to support them. They often stand in thoroughfares or sit on their bikes, leading to obstruction of pedestrian flow and sometimes spilling into streets. The lack of seating, shelter, or even clear queueing arrangements can cause both discomfort for the riders and disorder in the streetscape. Pedestrians navigate around parked bikes, and cars pulling in for curbside pickup must weave through these groups. In essence, a new user group has occupied spaces never intended for them.

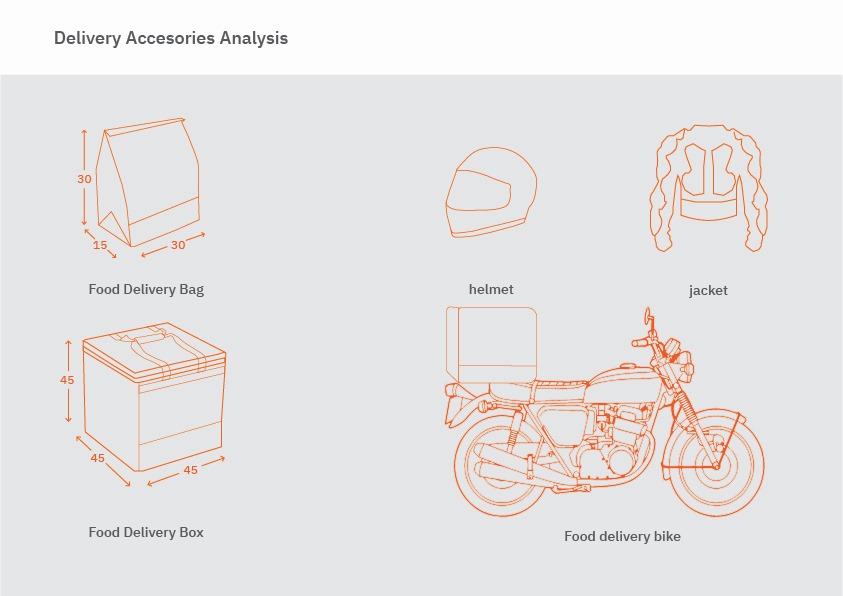

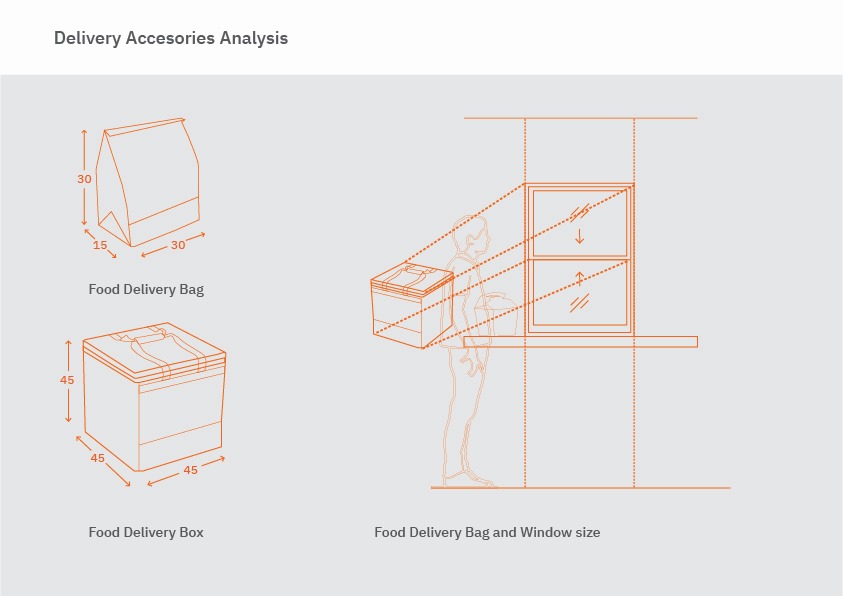

- Standardized Gear, Unstandardized Spaces: Interestingly, while the architecture is ad hoc, the delivery gear is somewhat standardized. Most riders carry insulated food delivery boxes or large backpacks with fairly common dimensions. A survey of typical equipment showed many rigid rear-mounted boxes are about 45 cm cubes, and insulated backpacks around 30–40 cm in width and height (capable of holding multiple food packages).

Figure 4: Typical delivery accessories – an insulated backpack (~30×30×15 cm), a standard rear-mounted bike box (~45×45×45 cm), plus rider essentials like helmets and jackets – present a relatively uniform set of dimensions. Riders’ essential gear like helmets and jackets is also fairly standardized. Any pickup infrastructure should accommodate these common sizes.

Despite this uniformity in their tools, current pickup points rarely take these sizes into account. Riders often have to place their box or bag on the ground or balance it precariously on a narrow ledge while transferring an order. A well-designed pickup station could include surfaces or slots tailored to these measurements (for example, a shelf that fits a 45 cm box securely, or hooks for hanging bags). Likewise, bike sizes themselves are relatively small (a typical motorbike or scooter is about 70 cm wide), meaning it is feasible to allocate very narrow parking or waiting bays for them – yet few locations do so today.

- Hygiene and Maintenance Issues: Another observed phenomenon is the challenge of keeping the delivery process clean and efficient without designated infrastructure. For instance, riders sometimes need to repack orders or add condiments/drinks to bags, and with no counters available, this happens on top of trash bins or bike seats. Similarly, there is no place to discard melted ice packs, spilled food, or other waste from the delivery process, leading to occasional litter around popular pickup spots. On the maintenance side, the high frequency of trips means bikes require regular refueling and servicing, but there are no dedicated service pods or bike repair stations provided by the city or the delivery companies. Everything is left to the individual – a sharp contrast to, say, taxi fleets that often have central garages or rest areas. This lack of support infrastructure is a spatial challenge: if one compares the city to an ecosystem, these delivery bikes are a new species introduced without any habitat planning.

In sum, the current urban condition around food deliveries is one of misalignment: the hardware (bikes, boxes, gear) has evolved and standardized to optimize speed and capacity, but the software (city design and architecture) lags behind. The result is inefficiency and friction – wasted time as riders search for parking or struggle with ill-suited pickup setups, and a sense of chaos for passersby and other users of the space.

A Proposed Design Code for Pick-Up Infrastructure

To bridge this gap, INJ Architects – through the Last Meal project – proposes a set of design guidelines (an urban design code) for integrating food delivery infrastructure into architecture. The aim is not heavy-handed regulation, but a constructive toolkit that cities and businesses can adopt to create a more orderly, efficient system benefitting all stakeholders. Key components of the proposed code include:

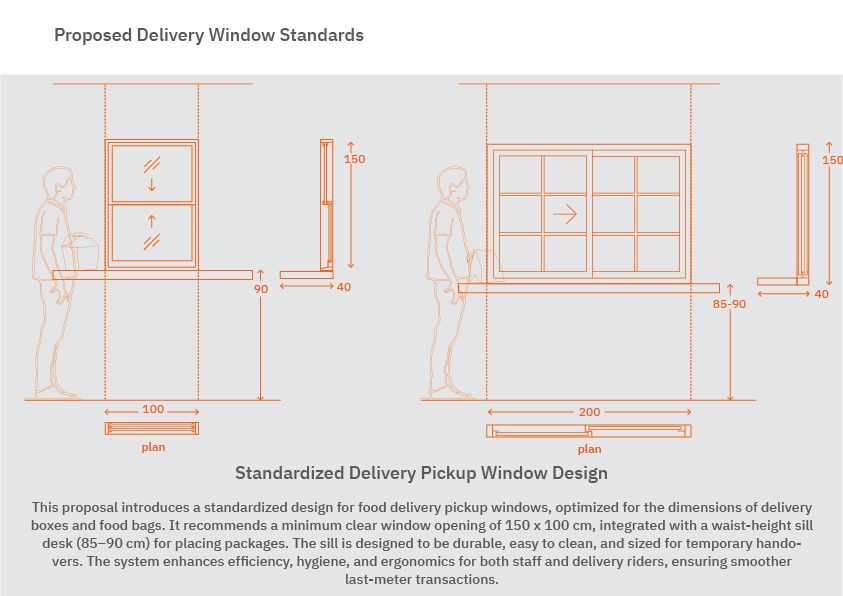

1. Standardized Pickup Windows

Every restaurant or food outlet with significant delivery volume should incorporate a dedicated delivery pickup window or hatch, separate from the main customer entrance. This window would be optimized for handovers:

- Ergonomic Height: The window sill or counter should be approximately 85–90 cm above ground (waist height), a comfortable level for standing adults to pass items back and forth. This height aligns with the average courier’s position whether on foot or even seated on a low scooter.

- Sufficient Opening Size: The window opening should be generous – the proposal recommends at least 100 cm wide and 120–150 cm tall – to accommodate bulky delivery bags and allow multiple items to be passed through at once. A wide, tall opening also provides a clear line of sight and communication between staff and riders.

- Integrated Shelf: A sturdy shelf or ledge should extend from the window on the exterior side, providing a surface to briefly place packages or a rider’s bag. For example, a 30–40 cm deep shelf can hold a 45 cm delivery box securely. This relieves couriers from juggling items and allows them to double-check contents safely before departing.

- Weather Protection & Visibility: The window design should include an overhead canopy or awning to shield the handover area from sun and rain – a simple addition that greatly improves comfort in climates like Riyadh’s. Good lighting and clear signage (e.g. “Delivery Pick-Up”) are also critical, ensuring riders can locate the pickup point quickly, even at night.

The lack of standardization in food delivery windows causes inefficiencies and discomfort for riders. INJ Architects proposes formalizing the “Pick-Up Window” as a new urban code element.

Figure 5: Proposed standard for a delivery pickup window, featuring a large pass-through opening (~150×100 cm) with an exterior counter at ~90 cm height. This design facilitates easy, ergonomic transfer of food parcels, improving speed and safety at the restaurant interface (INJ Architects, 2025). The ergonomic placement allows riders to receive orders without awkward bending or delays. Standardizing such windows citywide would greatly streamline last-meter deliveries.

2. Designated Rider Waiting Zones

Just as drive-thru restaurants provide waiting lanes, urban restaurants should have a defined area for delivery couriers to wait for orders. This could be:

- A Marked Zone on the Sidewalk or Curb: City regulations can require that any eatery above a certain volume of app-based orders has a demarcated waiting area outside. This might be a section of widened sidewalk or a curbside pull-out where a few motorcycles can stand without impeding pedestrians or traffic. Painted pavement markers or simple railings could indicate the zone.

- Shelter and Amenities: Ideally, this waiting area should include some basic amenities: an overhead canopy (even a simple awning attached to the façade) to provide shade, and perhaps a bench or lean-bar for riders to rest while waiting. These additions treat couriers as valued participants in the urban environment, not nuisances to be ignored. Some forward-thinking cities have already begun creating such facilities – for instance, Dubai recently introduced air-conditioned rest cabins for delivery riders, complete with water dispensers and phone charging stations to help them recharge in the summer heat [7][8].

- Queue Management: The design code suggests using simple technology or signage for order queue management. For example, a digital screen or a numbered ticket system at the pickup window can organize which rider is next, reducing crowding and confusion. Even without high-tech solutions, clear ground markings (like footprints or bike icons on the pavement) can intuitively space out waiting riders. Where space allows, installing a small service window directly linking the kitchen’s packing area to the exterior pickup zone is an ideal way to keep delivery traffic fully separate from dine-in operations [9]

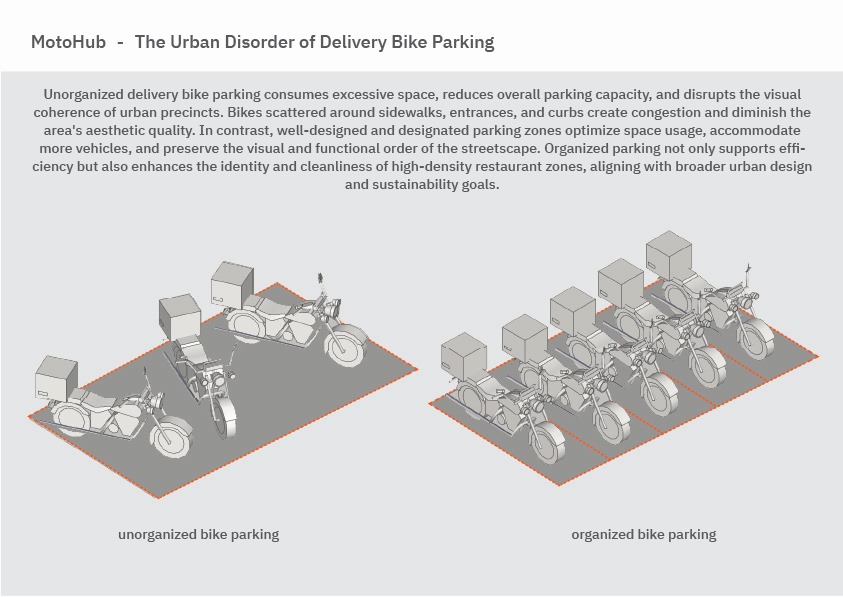

3. Parking and Mobility Integration

An oft-overlooked aspect is where the delivery bikes stop when picking up:

- Dedicated Bike Parking: Instead of motorcycles crowding randomly at storefronts, the code would require allocating a few short-term parking spots near the restaurant entrance, ideally off-street or in a designated bay. These spots can be very space-efficient – a single standard car parking space could fit 3–4 motorbikes. Providing this not only helps riders (no more circling the block or risking fines) but also keeps sidewalks clear. Urban restaurants in bike-heavy cities have started doing this, realizing that dedicated bike parking and convenient access allow delivery drivers to retrieve orders quickly without disrupting passersby [10].

- Traffic Safety Measures: The design code can work in concert with traffic authorities to ensure these pickup zones do not create blind spots or hazards. For instance, positioning the pickup window and bike parking on a low-traffic side street or alley (when possible), rather than directly on a busy arterial road, can reduce accident risk. Simple measures like installing convex mirrors at blind corners, or signage warning drivers of frequent bike crossings, also contribute to safety around these hubs.

4. Harmonizing with Accessory Standards

Architecture should adapt to the common dimensions of delivery equipment:

- Counter Height and Bag Room: As noted, a ~90 cm counter works well with an average person’s arm reach. Additionally, the interior layout of the restaurant should include a dedicated packing area for to-go orders, located near the pickup window. Within this area, tall locker-style shelving or cubbies can hold prepared orders (often in 30–40 cm tall paper bags) for easy grab-and-go. This keeps orders organized and at an accessible height for riders in a hurry.

- Gear Storage Hooks: Some code recommendations extend to the micro scale. For example, installing a few wall hooks or rack bars near the pickup window (outside or just inside) would allow riders to hang their helmet or bag briefly. This low-cost feature makes handoffs more convenient, preventing the notorious scene of a courier juggling a helmet under one arm while signing a receipt with the other. Similarly, if riders are allowed inside, an out-of-the-way corner with a small shelf or hook can keep their gear off the floor and out of foot traffic.

5. Support & Maintenance Facilities

Looking beyond individual restaurants, cities could incorporate support nodes for the delivery network:

- Rider Rest Stations: Taking inspiration from the UAE’s solar-powered rest cabins, municipalities might partner with delivery companies to set up modest “driver lounges” at strategic locations (e.g. busy commercial districts). These would be analogous to taxi stands or truck stops, providing couriers a place to take a break off the street. Amenities could include water fountains, vending machines or coolers for hydration, restrooms, and even an air pump for bike tires – features that some pilot projects have shown can be implemented sustainably (Dubai’s rest stations use solar panels and battery storage to run air-conditioning) [7][8].

- Charging Infrastructure: As the industry moves toward electric bikes and scooters (a transition already underway, since e-bikes are “the least polluting motorised transport option per mile [11]”), the urban design code can encourage or mandate the inclusion of charging outlets or battery swap kiosks at high-volume restaurants and rider hubs. Just as modern parking garages are updating to include EV charging for cars, a future-ready city would do the same for two-wheelers in the delivery fleet. This not only reduces emissions but also signals official support for cleaner delivery vehicles.

- Waste & Hygiene Provisions: To keep the system sustainable and clean, the guidelines call for waste bins and recycling points at major pickup locations, specifically for riders to toss packaging waste or damaged items. This prevents littering and acknowledges that the delivery process generates its own stream of waste that needs managing (e.g. plastic utensil packets, spilled drinks, melted ice packs). Regular city trash cans are often overflowing near popular takeout spots; a dedicated bin for couriers (emptied frequently) would help maintain sidewalk cleanliness.

In essence, the proposed code is about formalizing the interfaces – between restaurant and rider (windows/counters), between rider and city (waiting zones, parking), and between the delivery system and urban infrastructure (rest stops, power, waste management). These measures do not require heavy construction; they mostly involve smart tweaks, allocation of space, and small architectural additions. But cumulatively, they can greatly reduce the friction we see today. Importantly, these proposals are complementary to the operations of delivery companies, not antagonistic. By smoothing the “last 10 meters” of the delivery journey, restaurants get faster turnarounds, riders work more safely and comfortably, and customers receive their food hotter – a win-win for efficiency and quality.

Environmental and Urban Implications

Motorbike and bicycle delivery systems are often lauded for their potential to make urban logistics more sustainable. Indeed, replacing fleets of cars or vans with two-wheeled couriers can yield considerable environmental benefits. According to a recent industry report, deliveries made on bikes or scooters saved over 150,000 tonnes of carbon emissions in one year, compared to doing those deliveries by car [12]. By consolidating multiple food orders into one trip and using smaller vehicles, these services reduce the number of individual car journeys on the road. They also tend to ease traffic congestion: a scooter occupies far less space than a car, and can often avoid adding to jams by using bike lanes or fitting into tight parking spots. Cities that support two-wheeled delivery have noted a “virtuous cycle” of benefits, including reduced traffic and even improved street safety in some contexts [13].

However, the environmental promise of this decentralized delivery ecosystem can only be fully realized if cities adapt. Currently, the disorderly state of affairs can undermine some benefits:

- Urban Livability: There is also a broader ecological perspective: urban environment quality is not just about carbon metrics, but also about noise, air quality, and the orderly functioning of public space. Right now, the sight of throngs of riders crowding sidewalks and the incessant buzz of motorbike engines at all hours can be seen as a form of pollution in its own right – a visual and auditory intrusion into street life. A more organized system (with defined waiting spots, smoother handoffs, and eventually more electric, quieter bikes) will integrate this activity more harmoniously into city life. The goal is to make delivery riders a natural part of the urban ecosystem – akin to postal workers or public transit – rather than a source of friction or disorder.

- Idling and Circling: When riders cannot find a convenient place to pull over, they may circle the block or idle their engines in no-parking zones. This wastes fuel and adds emissions and noise at the very locations (restaurant entrances) that see high activity. By contrast, if a quick-stop parking zone is available, riders can turn off their engines sooner and avoid unnecessary driving around the block.

- Safety vs. Efficiency: Frequent accidents and near-misses not only endanger lives but can cause traffic snarls, emergency responses, and general inefficiency – all of which carry environmental and social costs. By designing safer pickup points (off the main road, with clear signage and sightlines), cities can reduce the chances of chaotic interactions between delivery bikes and other vehicles or pedestrians [11][14]. Smoother operations mean less unnecessary acceleration and braking, translating into lower emissions as well.

- Electric Transition: Infrastructure can accelerate the switch to cleaner vehicles. If a rider knows there are charging stations or battery swap facilities readily available, they are more likely to invest in an electric bike, which has zero tailpipe emissions and lower noise. Some delivery companies are already incentivizing this: for instance, DoorDash reports that e-bikes are the most energy-efficient form of motorized delivery, and it has partnered with e-bike manufacturers to offer discounts to couriers, encouraging this sustainable shift. Urban design should support such moves with the necessary charging provisions, ensuring that a growing e-bike fleet can be conveniently powered.

Crucially, we should acknowledge the positive: these riders represent a decentralized, human-scaled logistics network. They exemplify how small-scale mobility, if properly harnessed, can replace larger, more resource-intensive delivery methods. Studies in other contexts have shown that cargo bikes and courier bicycles can be not just greener but also faster than vans in dense city conditions[15][16]. The food delivery fleet is essentially a swarm of agile vehicles that, collectively, are stitching the city together in a new way. By codifying their needs in design standards, cities can amplify the ecological advantages (less pollution, less energy use) while mitigating the downsides (urban disorder, safety issues).

Conclusion: Toward a Supportive Urban Code

The Last Meal project by INJ Architects demonstrates that the rise of food delivery motorbikes is not merely a passing trend but a fundamental shift in urban logistics – one that demands a thoughtful architectural response. Rather than leaving this vital system to operate in legal and design limbo, we have the chance to proactively shape it for the better. The recommendations outlined – standard pickup windows, waiting zones, parking areas, and supportive facilities – amount to a new urban design code for last-mile deliveries. This code is envisioned as a collaborative effort: architects and urban designers working alongside city officials, restaurant owners, and delivery platforms to implement practical solutions.

It is important to emphasize the spirit of this proposal. This is not an antagonistic stance toward delivery companies or riders; on the contrary, it acknowledges the ecological and economic value they bring to our cities. Food delivery riders have kept urban life fed during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, reduced the need for countless car trips, and created a new sector of urban employment. Our approach simply asks: how can we tweak our built environment to better accommodate these modern couriers, for the benefit of all?

Moving forward, urban professionals are called to engage with this challenge. We should update building codes and development guidelines to include the small but crucial elements that the delivery era requires. Pilot projects – such as retrofitting a busy commercial street with a prototype “delivery hub” featuring multiple pickup windows and a covered rider waiting plaza – could showcase the impact of these ideas. Data collection, too, can help: cities might survey how many delivery pickups occur daily at major restaurants, using that to justify new guidelines (much as traffic studies justify new road rules).

In conclusion, Last Meal frames a constructive dialogue: the motorbike delivery phenomenon can be seen not as an urban nuisance, but as an opportunity to innovate in design and policy. By codifying simple yet effective design responses, we can transform the current Wild West of food delivery into a well-integrated part of city life – one where a courier on a bike is as thoughtfully accommodated in our architecture as a customer at a drive-thru. In doing so, we respect the dignity and needs of the riders, support the sustainability goals of our communities, and ensure that the convenience of on-demand food does not come at the expense of urban order. It is a call to action for architects and urbanists: the delivery bike may be small, but its impact is big – and so must be our design imagination in shaping its place in the modern city.

Sources:

- INJ Architects – Last Meal project research diagrams and field observations (2025).

- Thadani, D. (2024). Dabbawalla: Low-carbon urban delivery[1][2]. Congress for the New Urbanism.

- Arab News. Road safety fears amid Jeddah food delivery boom[4][5][6]. (2024, Feb 3).

- Chipman, L. (2025). Seamless Spaces: Restaurant Design Strategies for the Rise of Food Delivery[10]. Chipman Design Architecture Blog.

- Deliverect. 7 Ways to Improve Your Restaurant’s Design for Delivery[9]. (n.d.).

- SolarQuarter News. talabat Launches Solar-Powered Rest Areas For Delivery Riders Across UAE[7][8]. (2024, June 27).

- Supply Chain Digital. DoorDash Deliveries: A Major Step Towards Sustainability[12][11][14]. (2025, Mar 5).

- Wired. It’s Time for Cities to Ditch Delivery Trucks—for Cargo Bikes[15][16]. (2022, Sep 21).

Press Coverage

The Last Meal research has been featured in international architectural and design media outlets:

- Archinect – Last Meal: Designing Cities for the Delivery Era

Recognized for its originality in defining new spatial standards for delivery infrastructure.